In 2019, a team of astronomers released the first image ever taken of a black hole. It was hailed as a major breakthrough by the scientific community.

Now, the same team is revealing an entirely new view of the same object: a massive black hole at the center of Messier 87 (M87), a supergiant galaxy 53 million light years from Earth.

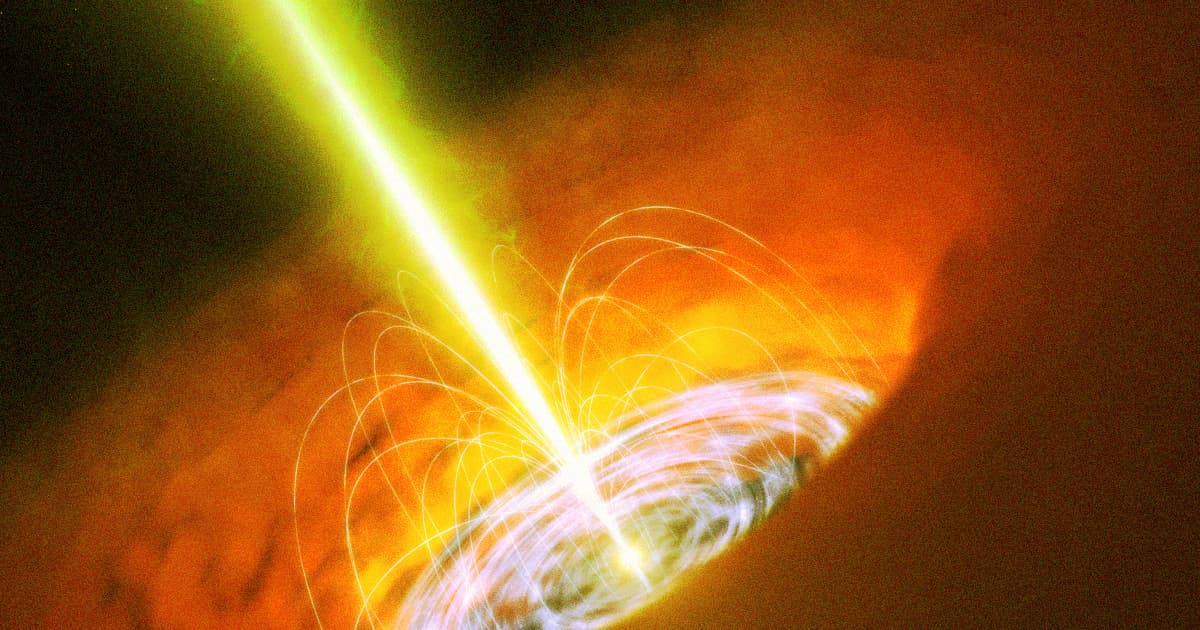

The new image, released by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration — an international team of scientists with over 300 members using a global network of telescopes to make unprecedented observations — shows the black hole in polarized light. In other words, it’s the black hole’s signature of magnetic fields.

By combining data from the network’s eight telescopes around the world, the team was able to zoom in so far that you’d be able to measure the length of a credit card on the surface of the Moon, according to a statement.

“We are now seeing the next crucial piece of evidence to understand how magnetic fields behave around black holes, and how activity in this very compact region of space can drive powerful jets that extend far beyond the galaxy,” said Monika Mościbrodzka, coordinator of the EHT Polarimetry Working Group and assistant professor at Radboud University in the Netherlands, in the statement.

“This work is a major milestone: the polarization of light carries information that allows us to better understand the physics behind the image we saw in April 2019, which was not possible before,” added Iván Martí-Vidal, another coordinator of the group and researcher at the Universitat de València, Spain.

Just like the lenses of polarized sunglasses, light becomes polarized when it passes through certain filters, and can allow us to reduce glare and reflections from bright objects. By viewing the black hole in polarized light, the team was able to make out far more details and map its magnetic field lines.

The new image could significantly further our understanding of black holes, particularly when it comes to the energetic jets spewing from its core, behavior that’s still a mystery to astronomers.

Any matter that doesn’t get gobbled up by the black hole itself gets captured and blown out into deep space, forming jets of energized particles. Those jets extend a whopping 5,000 light-years from the center of M87’s core, making it a galactic puzzle for astronomers.

“The observations suggest that the magnetic fields at the black hole’s edge are strong enough to push back on the hot gas and help it resist gravity’s pull,” said Jason Dexter, assistant professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, and coordinator of the EHT working group. “Only the gas that slips through the field can spiral inwards to the event horizon.”